This post is adapted from a talk I gave as part of the University of Rochester’s Music Interest Floor “Tune Up” talks. It’s about the history of the “pizza song” from Spiderman 2 for the PS2:

Quick music review:

- Why is the audio quality so bad?? Oh my god???

- This mess gets steadily faster as it goes on, but it also changes key whenever it speeds up, and I’m pretty sure that whoever made this gave so few shits that they just sped up the audio file instead of actually orchestrating it to go faster. So they aren’t really key changes, the pitch just shifts up whenever the tempo increases because the actual sound wave is being played back faster.

- It’s an incredibly monument to human apathy and I love it.

Anyway time for some music history.

Pizza, Pasta, Put It In A Box

You’ve probably heard this song before. It’s been a prominent meme for the past several years, especially with the growth in popularity of memes based off the Sam Raimi Spiderman movies. This song has been something of a meme for a lot longer than that though. I don’t want to make any assumptions about people’s familiarity with this tune, I’ve been cognizant of it for basically my entire life after I heard it parodied on Veggie Tales:

More recently (and memeily), back in 2016 or so the app ditty used this tune as one of it’s free music options. If you aren’t familiar, you’d give ditty some lyrics and it would sing them back to you set to a track of your choice. If you haven’t seen this classic before, enjoy (NSFW):

This isn’t just a meme, though, the tune has actual cultural and artistic merit. Here’s Pavarotti singing it in what is probably the most extra rendition of this ever recorded:

The Pavarotti recording contains this song’s original lyrics, but it’s really the tune that has seeped into some sort of multi-national cultural consciousness. Here’s a recording of the tune arranged as a solo piece for euphonium ft. a full wind band (probably the second-most extra rendition):

That last video also has an anime version. Obviously.

So, evidently, this tune is widely known and has been so for long enough that it’s clearly in the public domain and somewhat of a stock-melody, like one of those royalty-free tracks so many YouTube vlogs are set to. When you hear this song, what comes to mind? What associations are conjured up? Where would you guess it came from, and under what circumstances was it created? I always thought of it as the “Italian stereotype song,” like the audio version of this image:

I assumed it must be some Italian folk song that has existed among the common people for centuries. But then I got curious and googled it.

I assumed it must be some Italian folk song that has existed among the common people for centuries. But then I got curious and googled it.

Origins of an Elder-Meme

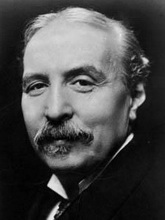

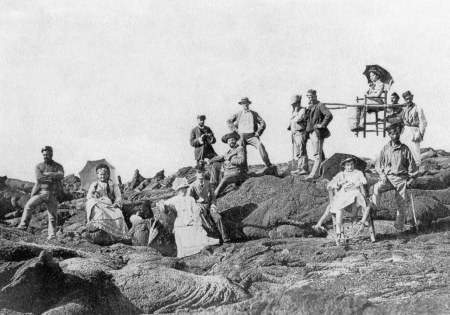

These two dapper Italians are Luigi Denza and Guiseppe “Peppino” Turco who wrote the music and lyrics, respectively, to this tune in 1880. Luigi met Peppino in Luigi’s hometown of Castellammare di Stabia:

That mountain in the distance is Mt. Vesuvius, Castellammare di Stabia is at the foot of it, and across the bay from Naples.

That mountain in the distance is Mt. Vesuvius, Castellammare di Stabia is at the foot of it, and across the bay from Naples.

Quick aside about trains: in 1880, trains were The Biggest Possible Deal. I’ll avoid blasting you with train history, but essentially, there was this huge global boom in railway construction in the second half of the 19th century. Railways were seen as emblematic of a new era of technology and the forward march of Progress and so international investors sunk insane quantities of money into the construction of railways. It was like akin to the hype surrounding cryptocurrency, but with more steel barons. In Italy, one of these rail projects was a funicular that ascended Mt. Vesuvius so that tourists could see the volcano’s (TO THIS DAY, DEFINITELY ACTIVE) caldera and I guess, have a picnic up there?

As you could expect there was a lot of excitement about this, almost to like a goofy degree. Journalist Peppino Turco, for one, thought this was really funny, so he wrote a song about the craze and called up his buddy Luigi to write some music for it, just in time for the funicular’s opening in 1880. Some accounts of this I’ve read say that Turco was commissioned by the funicular people to drum up hype, but other sources seem to suggest he was just in it for the memes, and that’s the version of events I prefer.

The song was called Funiculì, Funiculà, and these are the lyrics that Peppino came up with:

| Neapolitan | English (translation) |

|---|---|

Aissera, oje Nanniné, me ne sagliette, tu saje addó, tu saje addó Addó 'stu core 'ngrato cchiù dispietto farme nun pò! Farme nun pò! Addó lu fuoco coce, ma se fuje te lassa sta! Te lassa sta! E nun te corre appriesso, nun te struje sulo a guardà, sulo a guardà. (Coro) Jamme, jamme 'ncoppa, jamme jà, Jamme, jamme 'ncoppa, jamme jà, funiculì, funiculà, funiculì, funiculà, 'ncoppa, jamme jà, funiculì, funiculà! Se n'è sagliuta, oje né, se n'è sagliuta, la capa già! La capa già! È gghiuta, po' è turnata, po' è venuta, sta sempe ccà! Sta sempe ccà! La capa vota, vota, attuorno, attuorno, attuorno a tte! Attuorno a tte! Stu core canta sempe nu taluorno: Sposamme, oje né! Sposamme, oje né! (Coro) Jamme, jamme 'ncoppa, jamme jà, Jamme, jamme 'ncoppa, jamme jà, funiculì, funiculà, funiculì, funiculà, 'ncoppa, jamme jà, funiculì, funiculà! |

I climbed up high this evening, oh, Nanetta, Do you know where? Do you know where? Where this ungrateful heart No longer pains me! No longer pains me! Where fire burns, but if you run away, It lets you be, it lets you be! It doesn't follow after or torment you Just with a look, just with a look. (Chorus) Let's go, let's go! To the top we'll go! Let's go, let's go! To the top we'll go! Funiculi, funicula, funiculi, funicula! To the top we'll go, funiculi, funicula! The car has climbed up high, see, climbed up high now, Right to the top! Right to the top! It went, and turned around, and came back down, And now it's stopped! And now it's stopped! The top is turning round, and round, and round, Around yourself! Around yourself! My heart is singing the same refrain: We should be wed! We should be wed! (Chorus) Let's go, let's go! To the top we'll go! Let's go, let's go! To the top we'll go! Funiculi, funicula, funiculi, funicula! To the top we'll go, funiculi, funicula! |

Lyrics (and a lot of this post) courtesy of Wikipedia.

This song, today intimately tied to the perception of Italianness, is about taking a girl on a date to the summit of a volcano. That’s honestly pretty hardcore. I like the bit where the lyrics are like, oh, there is definitely lava up here, but you can just outrun it so it’s totally safe and fine. Also, there’s a lot of discussion of how the funicular ride itself is going and how that thing is operating, which I guess was novel enough at the time to be put to music. Evidently it was exciting enough to get the song’s subject to propose. Something I found neat is that the lyrics are not in Italian, they’re in Neapolitan, which is different from standardized “Italian” and still spoken widely throughout southern Italy. When Funiculì, Funiculà was written the unified Kingdom of Italy had only existed for about two decades, so it makes sense that Peppino would write the lyrics in the local language rather than the Tuscan-based one that the state had adopted as the national language less than a generation prior. If you were curious about what “funiculì, funiculà” means, those are just nonsense words there to make the word “funiculare” more fun to sing (Maybe they like verbify it? I don’t know Neapolitan).

Funiculì, Funiculà was presented at Naples’ 1880 Piedigrotta festival as an entry to the songwriting competition, and though it did not win it became immensely popular. Turco and Denza signed on with Italian music publisher Casa Recordi and in the first year sold over one MILLION copies of sheet music. For context, the phonograph was invented only four years before, so selling one million copies of your sheet music was as close to viral success as a songwriter was likely to get in 1880. The period of this song’s birth coincided with the beginning of large-scale emigration of southern Italians around the world, and they brought Funiculì, Funiculà, along with other popular Neapolitan songs, along with them. Thus knowledge of Funiculì, Funiculà was spread to all corners of the globe.

Italian as Pizza Pie?

Since 1880, Funiculì, Funiculà has become intimately associated with the Italian stereotype. My favorite example is the following piece from the soundtrack of 1993’s Super Mario Bros. (skip to about 1:27):

In this part of the film, the Bros. are engaged in a car chase, and composer Alan Silvestri (of Back to the Future and Avengers sountrack fame) made the baffling decision to insert a quote of Funiculì, Funiculà in a minor key just to remind you: “hey, I know this scene is tense, but don’t forget, they’re Italian”. It’s really weird, but the fact that Silvestri thought he could pull that off is evidence of the tune’s iconic Italianness. What is particularly interesting, to me, is that Funiculì, Funiculà conjured up this association basically right off the bat. Growing up, I always assumed it was a traditional Italian folk song, while the reality is that it was written, very deliberately and maybe as a joke and for monetary gain, in the modern era. Given that 1880 was pretty long ago, I don’t want to claim that those two things are mutually exclusive. In 1954 the International Folk Music Council defined folk music as

"The product of a musical tradition that has been evolved through the process of oral transmission. The factors that shape the tradition are: 1. Continuity which links the present with the past; 2. Variation which springs from the creative impulse of the individual or the group; and 3. selection by the community which determines the form or forms in which the music survives." - Isabelle Mills, Canadian Journal of Folk Music

So is Funiculì, Funiculà folk music? According to this definition from the International Folk Music Council, yes!… in 2019. But it probably wasn’t immediately folk music when it was originally composed. The funny thing is: it was so catchy back then people just assumed it was.

Enter Richard Strauss, responsible for the following piece of music you’ve definitely heard:

Strauss was a famous German composer and conductor of orchestras even in his own time. In the 1880s he went on a tour of Italy and heard some folk music that he really liked and incorporated it into his tone poem Aus Italien. This is what the section “Neapolitan Folksong” sounds like:

This was first performed only SIX YEARS after the publication of Funiculì, Funiculà. This is like if someone was visiting the US for the first time in 2019 and heard Old Town Road everywhere they went, so they went home and incorproated it into their multi-movement symphony as a traditional example of American country music. Luigi Denza found out about this and SUED Strauss for using his copyrighted material without his permission, and won in Italian court. Strauss was forced to pay Denza a royalty fee. Maybe Strauss was just a dirty plagiarist, except…

RIMSKY-KORSAKOV ALSO DID THIS:

There’s something about Funiculì, Funiculà that is so innately Italian that people around the world assumed it must be an intrinsic part of their culture. And now - it is. It’s like Denza was able to tap into the metaphysical ichor of the concept of Neapolitanness and draw forth its true shape into our world via song. Denza did outlive Rimsky-Korsakov, but doesn’t seem to have ever pressed charges like he did with Strauss. Russia is much farther from Italy than Germany, so maybe it was just too much of a hassle? Maybe this was a pre-Disney age in which copyrights could actually expire? But maybe, after almost 30 years, Luigi Denza realized just how ubiquitous his composition had become and decided to let it slide - after all, he wrote a piece of music that remains inextricably associated with his city and people almost even today, 140 years later.

Epilogue

Mt Vesuvius is and has been a very active volcano. Regular tremors and minor eruptions caused the Mt. Vesuvius funicular to need fairly regular repairs. The funicular operated with increasing erraticism until 1944, when an eruption of the volcano completely destroyed both the rail and the entire town of San Sebastiano. Due to the war, construction priorities shifted and the funicular was never rebuilt.

Some sources:

- https://www.vesuvioinrete.it/funicolare/e_funicolare_storia.htm

- http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/luigi-denza_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/

- http://www.napule-de-canzone.com/

- http://cjtm.icaap.org/content/2/v2art5.html

- https://www.earthmagazine.org/article/benchmarks-march-17-1944-most-recent-eruption-mount-vesuvius